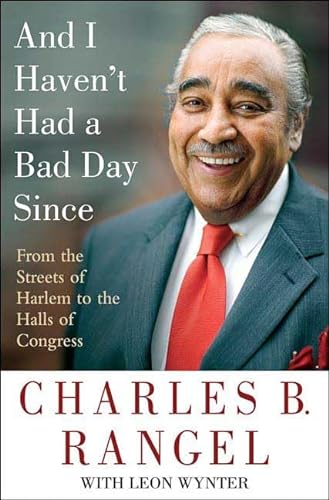

Items related to And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets...

A charming, natural storyteller, Rangel recalls growing up in Harlem, where from the age of nine he always had at least one job, including selling the legendary Adam Clayton Powell's newspaper; his group of streetwise sophisticates who called themselves Les Garçons; and his time in law school--a decision made as much to win his grandfather's approval as to establish a career. He recounts as well his life in New York politics during the 1960s and the grueling civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery.

With New York street smarts, Rangel is a tough liberal and an independent thinker, but also a collegial legislator respected by Democrats and Republicans alike who knows and honors the House's traditions. First elected to Congress in 1970, Rangel served on the House Judiciary Committee during the hearings on the articles of impeachment of President Nixon, helped found the Congressional Black Caucus, and led the fight in Congress to pressure U.S. corporations to divest from apartheid South Africa.

Best of all, this is a political memoir with heart, the story of a life filled with friends, humor, and accomplishments. Charles Rangel is one of a kind, and this is the story of how he became the celebrated person and politician he is today.

He opens his memoir with a preface about the 2006 elections and an outline of his goals as chairman of Ways and Means. From day one he wants to put the public first so that more Americans can say they haven't had a bad day since.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

1My Beginnings Family Roots Through Junior High SchoolMy family hails from miscegenated roots in Accomac, the seat of Accomack County, Virginia, on the rural DelMarVa peninsula. If the peninsula is a stubby thumb of land sticking 180 miles straight down the coast, right below the point where the borders of Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania meet, then Accomac is smack in the middle of its overgrown fingernail, the last 75 miles that encloses the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. By the map, Accomac is just 180 miles from the U.S. Capitol, but by road, history, and economics, it's much closer to Richmond, the ex-capital of the Confederacy.Then as now, the wealth of Accomack County comes from the land and the accumulated labor of African-Americans since slavery times. The tiny county raised 5 percent of all Virginia's chickens and grew almost half of Virginia's cash vegetable, corn, and melon crop in 1992. The 2000 census also said it was 32 percent black, 63 percent white, and just under one percent any kind of mixture. But everybody knows the numbers don't tell the real story.Accomac, Virginia, was a very strange place. It had a lot of relationships that were a lot stronger than anything you could get by getting married or in court. They had a lot of respect for people who simply had children and took care of them, whether they were married or not. And, from slavery times, a lot of those children were fathered by white landowners on black women. I think that attitude made it easier for everyone to live together, separate and, of course, unequal, bound to the same isolated piece of land, without a great need to ask a whole lot of questions about who was what to whom.In Accomac everybody was related to one another. My great-grandfather Frazer Wharton, who the pictures indicate I favor the most, had a white father. Frazer had his first child, my grandfather, by his first wife, Mary Dye, around 1893. Then he married another lady and had fourteenchildren. I'm not sure how Frazer managed to get all this land in Accomac, but I assume it came from the white Wharton clan that gave him his name. Except for a couple of uncles of mine who later passed for white, I still don't know much about the white Whartons. I grew up assuming that my grandfather was a scion of a proud black landholding gentry. Oh, was my mother proud of being a Wharton, hot damn! "Blanche Mary Wharton Rangel," she'd reply when formally asked her name.As a child, from the time I was seven to about age fifteen, the family would have me and my sister down there for the summers. They called it Whartonville, because the Whartons ran everything. I remember the farm people who would come into town and get drunk, and Frazer Wharton would get them out of jail. It was another world, the rural Deep South in the late depression years, or maybe two worlds away from Harlem. In Harlem, fruits and vegetables came to you, rolling by your house on a paved road, on a cart pushed by some European immigrant shouting in a foreign accent. In Accomac, you went down dirt roads to get your food from the land, with no whites of any kind in sight.In Harlem there were corner bars and rent parties and dance halls for celebrating the end of the workweek, or to get away from having no work at all. In Accomac there were county fairs. Oh, those fairs! It was just like in the movies--think Giant with Liz Taylor and Rock Hudson, or, better still, the movie version of the musical State Fair. Except everything and everybody was black. Oh, the pies, the crabs, and the corn--all that food and entertainment and all the drinking! I'd go there with my granduncle George, who liked to squire his little nephew from the big city around town. He was really the bad boy of the whole clan. He ran a little social spot in town, a kind of cross between what we called a candy store in Harlem and a nightclub. And he drank a lot of liquor. He'd get drunk at the fair and then forget where he left me. You know, something about drinking and then misplacing your kids must run in my family, because years later my uncle Herbert would sometimes do the same thing to me up in New York.In Accomac it seemed as if everyone but Uncle George worked the fields. When my sister and I were down there, everyone got up at five o'clock in the morning. If we wanted to eat with them, we had better be up early, too. Actually, they'd leave a cold ham on the table, maybe some fried apples in the frying pan. But then everyone hit the fields, and they worked hard. They took it very seriously, and they had us out there taking it seriously, too. I remember how we weren't supposed to eat any of the strawberries we were picking. They'd get angry with you if you were talking or fooling around, and they'd raise hell. Of course, once the daywas over, and we'd come back in out of that sun, they'd love us to death. But when they were working, they didn't give a damn where you were visiting from; if you were there and you were eating, you worked hard in the fields.If only for that reason, I made sure I spent my time hanging with Uncle George.Uncle George used to visit a lot of people at night, and leave me in the car. One time I ran the damn car into a tree while I was waiting. But he was so bad, he just said, "Forget about it." He didn't give a care about nothing. Uncle George! He had this place--I guess you'd call it a roadhouse--that served hot dogs and beer but no hard liquor. They had music going, and people would come, buy their cigarettes and soft drinks, and socialize. I don't recall thinking much about it at the time, but it must have felt a whole lot like the action on a Harlem street corner, and that was damn sure more my speed than picking produce.And Uncle George thought my coming from Harlem made me something special, gave me what we now call street smarts. And then I caught some guys stealing money from him one time, and that did it. He fired the guys, and bragged about how it took a kid from Harlem to get these thieving sons of bitches out of his business.So these are my grandfather's roots, but he didn't like the farm life that Accomac offered him. His name was Charlie Wharton, and I guess he could have stayed and staked a claim to some of that land. But one day when he was sixteen, he reached down, picked up a good handful of that dirt, and let it crumble through his hand. Then he looked up at his father and said he didn't want any part of it. That's the story he told me about getting out of Accomac, over and over through the decades. He basically went a couple hundred miles up the coast, to Atlantic City, New Jersey, and found work as a waiter. Later on he met this pretty gal, Frances, my grandmother, whom I never knew. She was from Savannah, Georgia. He brought her to New York, and had two children--my mother and her older brother, Herbert. They were living someplace in Hell's Kitchen, because that's where the blacks were at that time, before they started moving up, and uptown. My uncle was born in 1902, my mother in 1904. When my mother was two years old my grandmother died giving birth to a third child, who didn't survive. About 1923 my grandfather left Hell's Kitchen and moved to 132nd Street, where he bought a brownstone.Now, for the longest time he would have me believe that he didn't have access to any money to afford to buy that house, but his father, Frazer, came up to New York and signed a note for him. My grandfather put a down payment on the house, and he had to pay off that note.These are stories my grandfather told me in the kitchen, when he'd be drinking. Often, from down in his cups, he would go on about all he had done for my mother and my uncle Herbert, and how neither one of them appreciated it.My grandfather would never learn how to use the word love. Ever. But he did talk a lot about how he had to fight the authorities to keep his kids. Apparently the child welfare officials of the day were always trying to take my mother and Uncle Herbert from him because he wasn't married. Years later he would tell me stories about all the girlfriends he kept around the house when my mother and uncle were children. He'd go on about how they all had boyfriends, and he knew it. But he tolerated them, because all he cared about was having someone around to take care of those kids. Hell, he wasn't even around half the time, because he was out trying to make ends meet for them. To hear him tell it, the gals thought they were working him over, and he thought he was working them over. They may have thought they were cheating on him. But all he was concerned about was maintaining a minimum acceptable domestic environment for his children's sake. He wasn't looking for love; he was looking for someone to be there for those kids so he could go out and work.Somewhere along the line he met this lady, Miss Indie, we called her. I don't remember where she was from, but she was the force that straightened him out. He married her, and she really structured his life. She got him to take a civil service examination, which at the time involved picking up dumbbells, to qualify for an elevator operator job. She also got him to join a political club, and then to go for the job running an elevator in the Criminal Court building downtown. He put in about thirty-five years on that job before he retired. In fact, it was trying to help him keep that job just a little longer that caused me to take my very first step into politics.When he turned sixty-five, and they were trying to force him to retire, I had to go hat in hand to the neighborhood Democratic political club to plead for an extension. What happened was that I had signed a petition supporting an insurgent candidate for party office, someone who was not part of the regular organization. I didn't know what the hell I was signing. I was in law school, and I had not a clue about how clubhouse and Democratic machine politics worked. But they made a big deal out of it. It just happened that insurgents were the only guys who came by the house, always bearing petitions and asking us to sign. So I had signed. But the local captain made it abundantly clear that he had checked the names on that petition, and it looked like I was an upstart who was going against the regular organization. Nowadays, in mostplaces in New York, it seems like nobody knows who is who, much less who signed what, at the precinct level of politics. But back then, in Harlem, precinct- and club-level politics were like church-congregation or family-clan politics--no disloyalties went unnoticed or unrecorded, and people had memories like elephants. Even I remember it like yesterday. It was then called the New Era Democratic Club, and a few years later I'd make my first mark in politics by going up against its leader, Lloyd Dickens.My grandfather had actually signed the right petition, because he knew the precinct captain. And so he was right pissed at me for making waves that might sink his civil service job early--for no good reason. They would not give it to him until I came to the club--contrite--and asked forgiveness for my transgression. But it didn't stop there. They actually made me go to the Democratic leader of New York County, Carmine DeSapio, for the extension. They sent me to a guy who had something to say about making presidents of the United States, just to let one old black man in Harlem keep running an elevator for a few more years!The whole thing really teed me off, until I saw how petty it all was. That's just how disciplined they were back then, because for generations they maintained power over people down to the smallest detail--even a menial job--by counting every vote. It wasn't entirely about me at all. But there is also no question that once I showed up, going to law school and all, and voting in their precincts, they felt they needed to send me a message: "We've got our eye on you, son." They knew I was going someplace. I got that extension, and later, for years after I became friends with Carmine, I had something to tease him about. I also had my first taste of how dealing with powerful people gets things done, and might make you powerful, too.

Miss Indie opened up a little bakery-restaurant on Lenox Avenue. I never knew her well, but I understand that she was an entrepreneur. Ironically, after all those years of Grandfather keeping girlfriends as nannies for his kids, Miss Indie didn't really get along all that well with my mother or Uncle Herbert. Family history has it that Uncle Herbert once threw a brick through her store window, because he was mad about something or other. Uncle Herbert must have had a chip of some kind on his shoulder from puberty on. He ran away from home at least once as a teenager, and had a reputation as a street fighter. He joinedthe army at fifteen, and soon went up to Peekskill, New York, where he was trained. He served in the legendary 369th Infantry Regiment, the "Harlem Hellfighters," though he did not get to go overseas. Grandfather eventually convinced him to settle down and get a civil service job. They ended up working one block from each other, Uncle Herbert running an elevator in the New York State court building at 80 Worth Street, and my grandfather at the New York City Criminal Court building at 100 Centre Street. Uncle Herbert was married to one woman, my aunt Mariah--and had that elevator job and drank hard on the weekends--until the day he died. He had a bad relationship with his father, but in some ways he ended up doing the exact same thing with his life.My mother met my father in that brownstone on 132nd Street, where she lived with her father and stepmother. My father was working in the building as a handyman; she was fifteen or sixteen years old. She ran off with him and got married, though she was forced from time to time to return with me to the house she was raised in. My grandfather never, ever forgave her for that. While Uncle Herbert waged an open war for independence from grandfather's control, my mother went back and forth between cowering under her father's intimidation and slipping away on her own. It's hard to say who won most of the time, but I know who was always in the middle of their fight: me.My mother would buckle under a tongue-lashing from him, calling him "Father" and pleading with him. He'd cuss her out, and then I'd jump in and say "Don't you talk that way to my mother." She'd say, "Charlie, that's my father, you shut up." Grandfather would just laugh, because he just liked to piss me off. "I'll slap you to the floorboards, Blanche. I'll slap you to the floor," he'd go on. "No, you're not," I'd say, and run over to her, as he would be backing her down, jabbing his fist at her. "Oh, Father, please don't," she'd cry. But all it was was him showing me that he was in charge. He never hit her; he didn't have to to make his points. In fact, most of the time I was the one who got my behind whipped--by my mother, for interfering.Grandfather was content to simply scare the hell out of her, yelling and balling up his fist at her. He was short and my mother was short--he would have so much fun just intimidating her. And I would really go at him. I know he didn't dislike me for doing that, but it created an atmosphere of unpleasantness. Grandfather was forever giving me chores to do--clean the steps, sweep the street, march up to the Bronx over the Madison Avenue bridge to buy day-old bread, go downstairs to get coal for the fire, gather horse manure from the street for his backyard garden. On reflection, the fact that he would raise hell with me showed that he really care...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherThomas Dunne Books

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0312372523

- ISBN 13 9780312372521

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0312372523

And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0312372523

And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0312372523

And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0312372523

And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 320 pages. 9.50x6.25x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0312372523

And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0312372523

And I Haven't Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0312372523

AND I HAVEN'T HAD A BAD DAY SINC

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.2. Seller Inventory # Q-0312372523