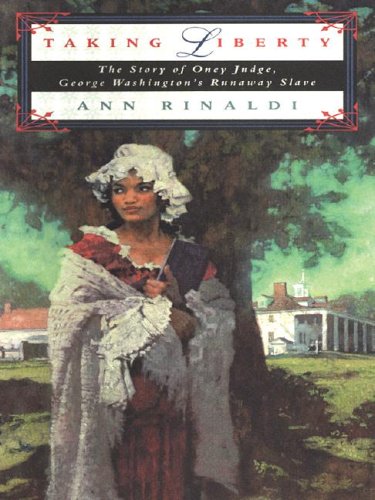

Items related to Taking Liberty: The Story of Oney Judge, George Washington&#...

As part of the staff of George and Martha Washington, Oney is referred to as a servant, not a slave, and when she becomes Martha's personal servant her status in the household is second to none. But, slowly, Oney realizes that -- regardless of what they call it -- it's still slavery, and she must make a choice. Told with immense power and compassion, this is the extraordinary true story of one young woman's struggle to take what is rightfully hers.

580L

(AR) For ages 12 and up

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

1775

Mount Vernon, VA

One day when I was three, my mama took me by the hand and dragged me to the slope of lawn that ran down to the river in front of the mansion house.

It didn't even have the piazza on yet. There was lumber and stone to one end, and builders working. She put her hand on the back of my neck, the way you hold a chicken just before you're about to chop its head off.

"You see that house, Oney Judge?" she said to me. "Do you?"

Well, I saw it, all right. For me and all the other little children on the place it was always in our line of sight. Like the Throne of Grace the mistress was always reading about in her Bible. We couldn't help but see it. It was there when you woke up at dayclean, and in the night you could see it in the mists from the quarters, candles glowing in the long windows.

"Yes, Mama," I said.

"Well, you just take a good look, Oney Judge. 'Cause that house is where you gonna work when you get old 'nuf. You ain't gonna be no hoe Negra. You gonna be a fine mistress of the needle, workin' in that house for the mistress. Like your aunt Myrtilla do. And me. And Charlotte. And that's why I want you inside now, plyin' your needle, and not in the quarters listenin' to those tall stories that old no-'count Sambo Anderson be tellin' you."

"He tells me about Africa, Mama."

She hit me in the ear. "You doan need to know 'bout Africa. You here, not there. And if'n you doan wanna spend your grown-up days trudgin' in the hot sun and pullin' weeds all summer, you best listen. You hear?"

All I heard was a ringing in my ear. But she was mouthing more words, and I knew they weren't good. And if I didn't say yes, I'd get another hit in my other ear. So I nodded my head yes. And I promised I would practice my stitching. And she walked around to the back of the house to go in and have her morning time of sewing with the mistress and my aunt Myrtilla and Charlotte. Because they were all mistresses of their needles.

Other things about my first years on the place I disremember. But I know of those things. I suspect I was told them by Aunt Myrtilla.

Some was told by old no-'count Sambo Anderson, who hunted and trapped and wore gold rings in his ears and adorned his face with tribal scars and tattoos and was anything but no-'count to me and the other children. Because he was a saltwater Negro, come from Africa, he had great esteem on the place. So that everyone, Negro and white alike, listened when he spoke.

Some things were told to me by One-Handed Charles, who could salt fish better than anybody with two hands. Some by Nathan, who worked in the mansion kitchen with Hercules, the cook. And some by Lame Alice, who mended the fishing nets.

It was Nathan who told me the business of "first and second mourning."

It seems I had practiced with my needle enough to be allowed in the mistress's bedchamber early of a morning with Mama and Aunt Myrtilla and Charlotte. This was a privilege given to few Negro women. All Negroes who worked in the house had to be not only the best at their chores, they had to be mulatto. Which, I soon learned, meant half white.

I was half white because of my daddy. He came from England. All'st he ever talked about was England. One time I heard him telling my mama about a place called Newgate. I thought my daddy was a squire, like the Fairfaxes, who lived next door. They came from England and they were fancified gentlemen.

I thought Newgate was his estate. And that someday he would take me and Mama there.

But when you play with other children, be they Negro or white, they soon set things right.

"Newgate is a prison," the other Negro children told me. "And your daddy's a convict. Our mamas say he was saved from hangin' by bein' sent to Virginia."

"Leastwise I know who my daddy is!" I shouted back. And Mama slapped me then, too. It didn't take much vexation for Mama to slap me.

"Is my daddy a convict?" I asked her.

"He's an indentured servant," she said.

It was early in the morning in the mistress's bedchamber. We hadn't had breakfast yet. And from belowstairs I could smell ham and coffee, and my stomach growled like the big, fluffy dog Sambo Anderson hunted with. The mistress's day started at seven because when her husband was home, he got up at four, made his own fire, wrote letters, then ate hoecakes and honey with her.

The mistress was belowstairs, seeing to the makings of dinner. Seems all they did was think about food in that house. The general and his lady had a regular fixation about food.

Winter sunshine poured in the windows. A fire burned in the hearth. Builders hammered away, making the south side of the house straight and true, the way the master said the corners of a house should be.

I sat on a rug trying to stitch the hem of a pillowcase.

"Mama, why do everybody in this house wear black all the time?" I asked.

"Doan ask so many questions," Mama snapped.

"But I like colors," I said. "Like the red of your head scarf and the amber beads the mistress sometimes wears. And the blue tea set she keeps on the sideboard."

"They all be in second mourning," Aunt Myrtilla answered.

Now, here was something. I stopped sewing. I liked morning, especially ones like this, when we came to the mansion house. I knew that soon Nathan would be bringing up a tray of food from the kitchen. Good food. Real coffee and fresh-baked bread and maybe some slices of ham. We didn't get much ham. Maybe some backbone, liver, what we called lights and whites called lungs. "Why do white folks get a second morning and we get only one?" I asked.

"Hush with your endless questions, child," Mama scolded.

At that moment Nathan came into the room. "Mistress send you all up some vittles." He set a tray of coffee, bread, butter, and ham on a table. Before he left, he squatted down beside me. Nathan was young, with bright eyes and short, fuzzy hair. Sometimes, when important company came, he got to wear livery. I knew what that was 'cause my Mama had helped sew it.

"There be two meanings to 'morning,'" he said. "One means 'the start of the day.' Like now. The other means 'a time of grief.' You grieve for somebody who died."

"Who died?" I asked.

He lowered his voice. "Lady Washington's daughter, Patsy. Last year. Got up from the dinner table in good spirits and fell on the floor in fits. In two minutes she wuz dead."

"What's fits?"

"It's what little girls get when they ask too many questions," Mama said.

"Daddy says it's the only way I'll learn."

"Your daddy puttin' notions in your head." Mama always said that.

"Your Mama made the first-mourning dress for Lady Washington," Aunt Myrtilla explained. "Stayed up all night makin' it. Gen'l give her five shillings for her work."

I knew that Negro servants often got shillings or pence for doing special work. I couldn't wait until I was old enough to earn such.

"This second-mourning dress she wearin' now come from Richmond," Charlotte put in. "It wuz too long. Your Mama fixed it. It gots a white collar. A little white allowed in second mourning."

"What about red?" I asked.

"No red allowed," Mama said.

"I see Master Jackie wearing a red vest under his black coat sometimes."

"You hush 'bout Master Jackie," Mama scolded. "Master Jackie does as he pleases. Doan need to 'splain to a little Negro girl what he do."

Master Jackie was dead Patsy's brother. Both were children from Lady Washington's first marriage.

"I like Master Jackie a lot," I said. "The way he come to our house sometimes and give me sweetmeats. The way he always find Mama in this house and ask her to sew a button on his vest. 'Member, Mama? Master Jackie come one time when he was in trouble in school? An' you were sad 'cause Daddy was away?"

"You hush 'bout that!" Mama snapped.

I hushed.

"You come on down to the kitchen with me now, honey," Nathan said. "And I'll give you a sweetmeat." He reached out his hand. He was favored because of the way he could make rock candy. In the kitchen he had a teakwood barrel full of long strings of glistening rock candy. And he used it to make rich brandy sauces for plum puddings.

"Miss Patsy die of the falling sickness," he told me on the way down. "Dr. Craik give her mercurial tablets, but they do no good. No more talk 'bout dyin', now. You can watch me ready a pair of ducks. Lady Washington says they must be laid by, in case of company."

"I'm afeared of Hercules," I said. Hercules was head cook, small, wiry, and full of moods. He threw pots and pans when things didn't go to his liking.

"Hercules not gonna hurt a pretty little girl like you. An' you listen, now, you're smart, too. Doan you ever stop askin' questions."

In the first years of my life I was happy. I lived in the two-story wood building on the service lane, north of the mansion. House families lived there. We had two chimneys, glazed windows, and finer blankets than those who didn't work in the house.

I was one of twenty-six children who belonged to women working at the mansion house, and I knew that house families were favored.

I knew my mama was favored. Everyone spoke good words about her round, pretty face. My daddy said she was taken with vanity, and it would bring her to trouble someday.

The first years of my life I took comfort and hope from the ordered world I lived in. And other than having to ply the needle, I could do as I pleased.

I and the other children would watch the builders working on the south end of the house, climb on the new lumber, hide in the quarry stone, until Mr. Lund Washington chased us away.

Mr. Lund, as we called him, was the general's kin. And he ran the place after the general went to war. He was strict, but I soon learned how to bring him around. When it was hot, I'd fetch a glass of lemonade for him from the kitchen. When it was cold, I'd bring hot coffee. Sometimes he let me go out on the river on the schooner that Father Jack, Sam, and Schomberg used to fish for shad or herring. Once he held me high up in his arms so I could see the cupola they were putting on the red-shingled roof. It was the highest point I could see. And I just knew it pointed to heaven.

But I was only three and a half. And too smart, Mama said, for my own good. "You gets that from your daddy. He may be bound to Mr. Washington, jus' like a slave, but leastways he kin be free someday. Me never, an' not you, either. So you best learn to sit on all those notions."

I did not want to sit on my notions. I was determined that no one would make me afraid.

Copyright © 2002 by Ann Rinaldi

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherThorndike Press

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0786255579

- ISBN 13 9780786255573

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages264

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Taking Liberty : The Story of Oney Judge, George Washington's Runaway Slave

Book Description Condition: Very Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 17784800-75