Items related to Democracy Reborn: The Fourteenth Amendment and the...

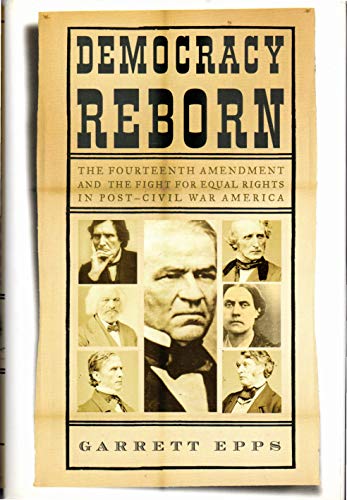

Democracy Reborn: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Fight for Equal Rights in Post-Civil War America - Softcover

A riveting narrative of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, an act which revolutionized the U.S. constitution and shaped the nation's destiny in the wake of the Civil War

Though the end of the Civil War and Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation inspired optimism for a new, happier reality for blacks, in truth the battle for equal rights was just beginning. Andrew Johnson, Lincoln's successor, argued that the federal government could not abolish slavery. In Johnson's America, there would be no black voting, no civil rights for blacks.

When a handful of men and women rose to challenge Johnson, the stage was set for a bruising constitutional battle. Garrett Epps, a novelist and constitutional scholar, takes the reader inside the halls of the Thirty-ninth Congress to witness the dramatic story of the Fourteenth Amendment's creation. At the book's center are a cast of characters every bit as fascinating as the Founding Fathers. Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, among others, understood that only with the votes of freed blacks could the American Republic be saved.

Democracy Reborn offers an engrossing account of a definitive turning point in our nation's history and the significant legislation that reclaimed the democratic ideal of equal rights for all U.S. citizens.

Though the end of the Civil War and Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation inspired optimism for a new, happier reality for blacks, in truth the battle for equal rights was just beginning. Andrew Johnson, Lincoln's successor, argued that the federal government could not abolish slavery. In Johnson's America, there would be no black voting, no civil rights for blacks.

When a handful of men and women rose to challenge Johnson, the stage was set for a bruising constitutional battle. Garrett Epps, a novelist and constitutional scholar, takes the reader inside the halls of the Thirty-ninth Congress to witness the dramatic story of the Fourteenth Amendment's creation. At the book's center are a cast of characters every bit as fascinating as the Founding Fathers. Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, among others, understood that only with the votes of freed blacks could the American Republic be saved.

Democracy Reborn offers an engrossing account of a definitive turning point in our nation's history and the significant legislation that reclaimed the democratic ideal of equal rights for all U.S. citizens.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Garrett Epps is the author of The Shad Treatment and The Floating Island: A Tale of Washington. He is the Orlando John and Marian H. Hollis Professor at the University of Oregon School of Law. He lives in Eugene, Oregon.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Prologue

Philadelphia 1787: Red Sky at Morning

From his vantage point in Paris, Thomas Jefferson had hailed the makeup of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in characteristic hyperbole. "It really is an assembly of demi-gods," he wrote to John Adams.

Perhaps. But by August 1787, the demigods were feeling tired and distinctly mortal. Since May 25, they had spent day after day in the small assembly room of the Pennsylvania statehouse, dressed in wool and broadcloth finery amid the humid swelter of Philadelphia--the new nation's cosmopolis, to be sure, but still in summer something of a fever port. To make the room even hotter, they had barred the windows, lest the revolutionary plan they were hatching--to scrap the entire American political system and replace it with a powerful national government--leak out before their work was completed. Day after day, they had marched through agonizing problems. Would the new government have no executive, multiple executives, or only one? That dilemma was solved by creating a powerful presidency custom-tailored for the convention's presiding officer, George Washington. Would there be a new system of federal courts? That one they finessed, by creating a Supreme Court and leaving the question of lower courts to the discretion of future Congresses. How would the new Congress be selected? The large and small states had compromised on this, creating a House apportioned by population and a Senate in which each state would be equal. Who could veto laws passed by Congress? They lodged this power solely in the president, just as the British reposed it in their king. What powers would Congress have? Nationalist delegates like James Madison wanted the Constitution to state that Congress would have the power to "legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual Legislation [and] to negate all laws passed by the several States." But delegates jealous of the powers of the states had forced a retreat, giving Congress a set of enumerated powers that were designed to keep it out of local matters.

What we know about what went on in that small hot room is mostly revealed in handwritten notes taken by Madison, the strongest advocate of a powerful new national government. Many delegates took lengthy leaves of absence during the summer, drawn away by their own business affairs or the deliberations of the Continental Congress, meeting in New York. Not Madison. Day after day this earnest, brilliant little man was in his seat, scribbling in his odd abbreviated style what each delegate had to say about each part of the proposed new government. Night after night, while other delegates relaxed amid the pleasures of a city known for fine wine, sophisticated conversation, and beautiful women, Madison stayed at his desk, revising his notes and reviewing the historical record of federal republics, beginning with the Amphictionic League of ancient Greece and moving forward to the contemporaneous Dutch Republic. Madison's gifts to the new country include the plan of both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights; but even set against those triumphs, his handwritten notes represent an important legacy to the future.

Those notes spark many feelings in Americans today. There is exhilaration and pride, to be sure. These fifty-five men, who came from states with radically different interests and wildly divergent social systems, were patient, practical, and often eloquent. They were willing to listen to those who differed with them and to change their most profound ideas if the arguments on the other side seemed good--or the disagreement so profound that it might threaten the convention with failure.

The debates, however, also spark dismay and even shame. The demigods did not see how inequality of wealth and status, of sex and race, would poison the new republic they were building. A reader feels compassion, too, for men who were racing against chaos in the new country to build a structure for a future they could only dimly foresee. And finally, from time to time, there is puzzlement. Because amid the true debate--the cut and thrust of brilliant minds with differing views--there were repeated moments of reticence, when important questions about the future were floated by one speaker or another, only to fall dead without any response in the still dusty air of the hall. Such a moment came on September 12, after the convention had, with great labor, produced an all-but-final draft of the document to be adopted. Without warning, George Mason of Virginia (who would eventually refuse to sign the Constitution because he viewed it as a blueprint for "monarchy, or a tyrannical aristocracy") popped up to suggest that the convention should now produce a Bill of Rights. "It would give great quiet to the people," Madison records Mason saying, "and with the aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours."

Like marathon runners hearing that the finish line might be moved a couple of miles farther back, the convention received this idea in sullen silence. Not a single state delegation voted to proceed with drafting a Bill of Rights. It was a mistake; the lack of a Bill of Rights outraged many Americans, and came close to dooming the new Constitution to rejection.

But of all the lost voices of Philadelphia 1787, the one that should most haunt modern ears is that of Gouverneur Morris of New York, who rose on August 8 to say what many of the delegates knew in their heart, but deeply wished not to acknowledge or discuss.

Crowded as the delegates were in the small meeting room in the East Wing, there was something huge in it with them--an ill omen that no one truly wanted to acknowledge. As Philadelphia spring turned to summer, most of those present had come to realize that the infant republic carried within it the seeds of its own destruction, flaws that might strangle the child in the cradle, or destroy it years or even decades later.

When the delegates gathered, they had expected friction between the large powerful states like Virginia and New York on the one hand and the small states like New Jersey and Georgia on the other. That divide surfaced quickly and shaped the schemes for electing Congress and the president. But another less expected division appeared in Philadelphia--one that never went away again. On June 30, Madison noted that "the States were divided into different interests not by their difference of size, but by other circumstances; the most material of which resulted partly from climate, but principally from their having or not having slaves. These two causes concurred in forming the great division of interests in the U[nited] States. It did not lie between the large & small States; it lay between the Northern and the Southern. . . ."

The divide was not as simple as we might imagine today. There was no gulf between "slave states" and "free states" because in 1787 there was only one free state--Massachusetts, where a court decision had effectively throttled the institution in 1783. (Vermont, which had abolished slavery in 1777, was still an independent republic and would not join the Union until 1791.) There were slaves in all the other states--twenty thousand of them in New York alone. But there was a difference between North and South--the difference of climate Madison referred to. Slavery in the North was an embarrassment; worse than that, it was unprofitable. But in the plantations of the South, soil and rainfall favored the cultivation of cash crops for sale abroad--tobacco, rice, indigo and, more recently, cotton. Those crops could only be grown profitably with slave labor, and the planters who ruled the Southern states found that embarrassment lessened as profits increased. They were wed to slavery and zealous to protect it from any new government created in Philadelphia. The men sent by the South--led by Charles Pinckney and his cousin, General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, both of South Carolina--wanted a federal government that would have no power over slavery. More than that, the new government must be pledged to protect slavery as well. "S[outh] Carolina & Georgia cannot do without slaves," General Pinckney explained to the convention. Over and over during the weary months of constitution-making, the Southerners made their position clear: if they did not get protection and support for slave property, the South would not join the new Republic and the convention's program would fail.

The prospect of disunion was terrifying to all the delegates, Northern and Southern. Gouverneur Morris on July 5 had set out starkly what he saw as the stakes; they were not just national survival but perhaps the very lives of those present and their families. Disunion meant civil war and blood running in the streets. "This country must be united. If persuasion does not unite it, the sword will," he warned. "The scenes of horror attending civil commotion cannot be described, and the conclusion of them will be worse than the term of their continuance. The stronger party will then make traitors of the weaker; and the Gallows & Halter will finish the work of the sword."

But Southerners vowed they would risk disunion rather than give up the protections they sought. Northerners believed them; and so, link by link, they forged the multiple chains that would tie slavery to the federal government. Congress could control interstate and foreign commerce, but it would not be allowed to bar the import of slaves until 1808. Northern states were required to return runaway slaves to their Southern masters, even if slavery became illegal in the North. If the Southern states faced a slave revolt, the federal government was required to furnish troops to crush it. Congress could tax imports (which the people of the North depended on) but not exports--the cash crops that fueled the slave economy.

Many of the Northern delegates were embarrassed by the bargain they felt forced to strike. But the discomfort did not break out into the open until the convention tackled the issue of apportionment. The new House of Representatives would be chosen "by the People of the several states." But power in the House was to be distributed according to population. Here the power of the slave states became more than embarrassing; it began to seem onerous. Led by the Pinckneys, Southern delegates at first insisted that every slave be counted in the state's population for apportionment; these human chattels, who could not vote or marry or enter into contracts or testify in court, were nonetheless entitled to representation in Congress--representation that their white masters would supply, gaining power in the federal government as a reward for their maintenance of a slave system. With a great show of magnanimity, the South at last consented to abandon the idea of full representation for its slaves. Instead, it would "compromise" at something called "the federal ratio," which had once been proposed by the Continental Congress for the apportionment of taxes. For each slave, the state would receive credit for three-fifths of a free citizen. As a result, one white voter in the South might have the same power as two or even three in the North.

Nor was that the end of it. Madison had proposed that the people elect the president; but the Southern interests feared being outvoted in those elections, too, and they supported another "compromise"--the president would be chosen by "electors," and each state would have the same number of electors as it had members of Congress. Thus the slaves who boosted Southern power in the House would also give it a heightened voice in the choice of the president as well.

On August 8, the "three-fifths compromise" finally pushed Gouverneur Morris over the edge of parliamentary politeness. Morris had warned the convention of the consequences of disunion, an apocalyptic vision of civil war and summary execution. Now he looked at the alternative--union on Southern terms--and he did not like that much better.

In 1787, Morris was a veteran revolutionary, though still only thirty-five. Born in New York, he had been selected as a delegate to the convention from Pennsylvania, where he had moved only ten years earlier. His figure was unforgettable. Well over six feet tall (his political enemies called him "the Tall Boy"), he was the only delegate who could match the convention's president, George Washington, in physical stature. His appearance was unforgettable, not only because of the good looks that attracted women to him throughout his life, but because a carriage accident had led to the amputation of his left leg seven years earlier. He would hoist himself aloft on a wooden leg and teeter above his colleagues as he spoke. Morris rose often--only Madison and James Wilson of Pennsylvania spoke more often than he did during the deliberations. And when he spoke, the members took notice--though not a few, no doubt, did so with as much disquiet as fascination. Because Morris not only spoke often, he spoke well, and, unlike many more practical politicians, he said what was on his mind.

One recent biographer, Richard Brookhiser, has called Morris "the rake who wrote the Constitution." Rake he was, both as a young man and in the years after Philadelphia, when he scandalized Paris with his affair with Adèle de Flahaut, a married woman who was also the mistress of the Revolutionary diplomat Talleyrand. As for the Constitution, he might better be called its "editor"--true authorship, if it lies anywhere, goes to Madison--but Morris's agile pen smoothed out the final version before adoption, adding, among other things, the felicitous words "We the People of the United States." Morris's constitutional effectiveness stemmed from his politics, which are even more worthy of note than his amours: he was that rarest and most useful of figures, a conservative who genuinely embraced radical change.

During the years before Independence, Morris had repeatedly sought to slow the mo...

Philadelphia 1787: Red Sky at Morning

From his vantage point in Paris, Thomas Jefferson had hailed the makeup of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in characteristic hyperbole. "It really is an assembly of demi-gods," he wrote to John Adams.

Perhaps. But by August 1787, the demigods were feeling tired and distinctly mortal. Since May 25, they had spent day after day in the small assembly room of the Pennsylvania statehouse, dressed in wool and broadcloth finery amid the humid swelter of Philadelphia--the new nation's cosmopolis, to be sure, but still in summer something of a fever port. To make the room even hotter, they had barred the windows, lest the revolutionary plan they were hatching--to scrap the entire American political system and replace it with a powerful national government--leak out before their work was completed. Day after day, they had marched through agonizing problems. Would the new government have no executive, multiple executives, or only one? That dilemma was solved by creating a powerful presidency custom-tailored for the convention's presiding officer, George Washington. Would there be a new system of federal courts? That one they finessed, by creating a Supreme Court and leaving the question of lower courts to the discretion of future Congresses. How would the new Congress be selected? The large and small states had compromised on this, creating a House apportioned by population and a Senate in which each state would be equal. Who could veto laws passed by Congress? They lodged this power solely in the president, just as the British reposed it in their king. What powers would Congress have? Nationalist delegates like James Madison wanted the Constitution to state that Congress would have the power to "legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual Legislation [and] to negate all laws passed by the several States." But delegates jealous of the powers of the states had forced a retreat, giving Congress a set of enumerated powers that were designed to keep it out of local matters.

What we know about what went on in that small hot room is mostly revealed in handwritten notes taken by Madison, the strongest advocate of a powerful new national government. Many delegates took lengthy leaves of absence during the summer, drawn away by their own business affairs or the deliberations of the Continental Congress, meeting in New York. Not Madison. Day after day this earnest, brilliant little man was in his seat, scribbling in his odd abbreviated style what each delegate had to say about each part of the proposed new government. Night after night, while other delegates relaxed amid the pleasures of a city known for fine wine, sophisticated conversation, and beautiful women, Madison stayed at his desk, revising his notes and reviewing the historical record of federal republics, beginning with the Amphictionic League of ancient Greece and moving forward to the contemporaneous Dutch Republic. Madison's gifts to the new country include the plan of both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights; but even set against those triumphs, his handwritten notes represent an important legacy to the future.

Those notes spark many feelings in Americans today. There is exhilaration and pride, to be sure. These fifty-five men, who came from states with radically different interests and wildly divergent social systems, were patient, practical, and often eloquent. They were willing to listen to those who differed with them and to change their most profound ideas if the arguments on the other side seemed good--or the disagreement so profound that it might threaten the convention with failure.

The debates, however, also spark dismay and even shame. The demigods did not see how inequality of wealth and status, of sex and race, would poison the new republic they were building. A reader feels compassion, too, for men who were racing against chaos in the new country to build a structure for a future they could only dimly foresee. And finally, from time to time, there is puzzlement. Because amid the true debate--the cut and thrust of brilliant minds with differing views--there were repeated moments of reticence, when important questions about the future were floated by one speaker or another, only to fall dead without any response in the still dusty air of the hall. Such a moment came on September 12, after the convention had, with great labor, produced an all-but-final draft of the document to be adopted. Without warning, George Mason of Virginia (who would eventually refuse to sign the Constitution because he viewed it as a blueprint for "monarchy, or a tyrannical aristocracy") popped up to suggest that the convention should now produce a Bill of Rights. "It would give great quiet to the people," Madison records Mason saying, "and with the aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours."

Like marathon runners hearing that the finish line might be moved a couple of miles farther back, the convention received this idea in sullen silence. Not a single state delegation voted to proceed with drafting a Bill of Rights. It was a mistake; the lack of a Bill of Rights outraged many Americans, and came close to dooming the new Constitution to rejection.

But of all the lost voices of Philadelphia 1787, the one that should most haunt modern ears is that of Gouverneur Morris of New York, who rose on August 8 to say what many of the delegates knew in their heart, but deeply wished not to acknowledge or discuss.

Crowded as the delegates were in the small meeting room in the East Wing, there was something huge in it with them--an ill omen that no one truly wanted to acknowledge. As Philadelphia spring turned to summer, most of those present had come to realize that the infant republic carried within it the seeds of its own destruction, flaws that might strangle the child in the cradle, or destroy it years or even decades later.

When the delegates gathered, they had expected friction between the large powerful states like Virginia and New York on the one hand and the small states like New Jersey and Georgia on the other. That divide surfaced quickly and shaped the schemes for electing Congress and the president. But another less expected division appeared in Philadelphia--one that never went away again. On June 30, Madison noted that "the States were divided into different interests not by their difference of size, but by other circumstances; the most material of which resulted partly from climate, but principally from their having or not having slaves. These two causes concurred in forming the great division of interests in the U[nited] States. It did not lie between the large & small States; it lay between the Northern and the Southern. . . ."

The divide was not as simple as we might imagine today. There was no gulf between "slave states" and "free states" because in 1787 there was only one free state--Massachusetts, where a court decision had effectively throttled the institution in 1783. (Vermont, which had abolished slavery in 1777, was still an independent republic and would not join the Union until 1791.) There were slaves in all the other states--twenty thousand of them in New York alone. But there was a difference between North and South--the difference of climate Madison referred to. Slavery in the North was an embarrassment; worse than that, it was unprofitable. But in the plantations of the South, soil and rainfall favored the cultivation of cash crops for sale abroad--tobacco, rice, indigo and, more recently, cotton. Those crops could only be grown profitably with slave labor, and the planters who ruled the Southern states found that embarrassment lessened as profits increased. They were wed to slavery and zealous to protect it from any new government created in Philadelphia. The men sent by the South--led by Charles Pinckney and his cousin, General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, both of South Carolina--wanted a federal government that would have no power over slavery. More than that, the new government must be pledged to protect slavery as well. "S[outh] Carolina & Georgia cannot do without slaves," General Pinckney explained to the convention. Over and over during the weary months of constitution-making, the Southerners made their position clear: if they did not get protection and support for slave property, the South would not join the new Republic and the convention's program would fail.

The prospect of disunion was terrifying to all the delegates, Northern and Southern. Gouverneur Morris on July 5 had set out starkly what he saw as the stakes; they were not just national survival but perhaps the very lives of those present and their families. Disunion meant civil war and blood running in the streets. "This country must be united. If persuasion does not unite it, the sword will," he warned. "The scenes of horror attending civil commotion cannot be described, and the conclusion of them will be worse than the term of their continuance. The stronger party will then make traitors of the weaker; and the Gallows & Halter will finish the work of the sword."

But Southerners vowed they would risk disunion rather than give up the protections they sought. Northerners believed them; and so, link by link, they forged the multiple chains that would tie slavery to the federal government. Congress could control interstate and foreign commerce, but it would not be allowed to bar the import of slaves until 1808. Northern states were required to return runaway slaves to their Southern masters, even if slavery became illegal in the North. If the Southern states faced a slave revolt, the federal government was required to furnish troops to crush it. Congress could tax imports (which the people of the North depended on) but not exports--the cash crops that fueled the slave economy.

Many of the Northern delegates were embarrassed by the bargain they felt forced to strike. But the discomfort did not break out into the open until the convention tackled the issue of apportionment. The new House of Representatives would be chosen "by the People of the several states." But power in the House was to be distributed according to population. Here the power of the slave states became more than embarrassing; it began to seem onerous. Led by the Pinckneys, Southern delegates at first insisted that every slave be counted in the state's population for apportionment; these human chattels, who could not vote or marry or enter into contracts or testify in court, were nonetheless entitled to representation in Congress--representation that their white masters would supply, gaining power in the federal government as a reward for their maintenance of a slave system. With a great show of magnanimity, the South at last consented to abandon the idea of full representation for its slaves. Instead, it would "compromise" at something called "the federal ratio," which had once been proposed by the Continental Congress for the apportionment of taxes. For each slave, the state would receive credit for three-fifths of a free citizen. As a result, one white voter in the South might have the same power as two or even three in the North.

Nor was that the end of it. Madison had proposed that the people elect the president; but the Southern interests feared being outvoted in those elections, too, and they supported another "compromise"--the president would be chosen by "electors," and each state would have the same number of electors as it had members of Congress. Thus the slaves who boosted Southern power in the House would also give it a heightened voice in the choice of the president as well.

On August 8, the "three-fifths compromise" finally pushed Gouverneur Morris over the edge of parliamentary politeness. Morris had warned the convention of the consequences of disunion, an apocalyptic vision of civil war and summary execution. Now he looked at the alternative--union on Southern terms--and he did not like that much better.

In 1787, Morris was a veteran revolutionary, though still only thirty-five. Born in New York, he had been selected as a delegate to the convention from Pennsylvania, where he had moved only ten years earlier. His figure was unforgettable. Well over six feet tall (his political enemies called him "the Tall Boy"), he was the only delegate who could match the convention's president, George Washington, in physical stature. His appearance was unforgettable, not only because of the good looks that attracted women to him throughout his life, but because a carriage accident had led to the amputation of his left leg seven years earlier. He would hoist himself aloft on a wooden leg and teeter above his colleagues as he spoke. Morris rose often--only Madison and James Wilson of Pennsylvania spoke more often than he did during the deliberations. And when he spoke, the members took notice--though not a few, no doubt, did so with as much disquiet as fascination. Because Morris not only spoke often, he spoke well, and, unlike many more practical politicians, he said what was on his mind.

One recent biographer, Richard Brookhiser, has called Morris "the rake who wrote the Constitution." Rake he was, both as a young man and in the years after Philadelphia, when he scandalized Paris with his affair with Adèle de Flahaut, a married woman who was also the mistress of the Revolutionary diplomat Talleyrand. As for the Constitution, he might better be called its "editor"--true authorship, if it lies anywhere, goes to Madison--but Morris's agile pen smoothed out the final version before adoption, adding, among other things, the felicitous words "We the People of the United States." Morris's constitutional effectiveness stemmed from his politics, which are even more worthy of note than his amours: he was that rarest and most useful of figures, a conservative who genuinely embraced radical change.

During the years before Independence, Morris had repeatedly sought to slow the mo...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHenry Holt and Co.

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 080507130X

- ISBN 13 9780805071306

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 78.76

Shipping:

US$ 5.06

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

DEMOCRACY REBORN: THE FOURTEENTH

Published by

Henry Holt and Co.

(2006)

ISBN 10: 080507130X

ISBN 13: 9780805071306

New

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.25. Seller Inventory # Q-080507130X

Buy New

US$ 78.76

Convert currency