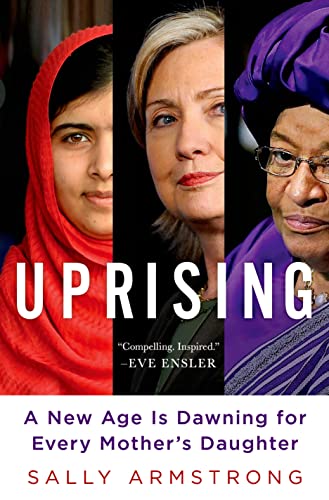

Items related to Uprising: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mother's...

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The Shame Isn’t Ours, It’s Yours

The first corner turning was realizing we weren’t crazy. The system was crazy.—GLORIA STEINEM

Rape is hardly the first thing I would want to mention after delivering the uplifting news that women have reached a tipping point in the fight for emancipation. But as much as major corporations now want women on their boards, and the women of the Arab Spring have flexed their might in overthrowing dictators, and the women of Afghanistan and elsewhere are prepared to go to the barricades to alter their status, sexual violence still stalks them. It doesn’t stop women from reforming justice systems, opening schools, and establishing health care. It doesn’t eliminate them from leadership roles or prevent them from acting as mentors and role models. But rape continues to be the ugly foundation of women’s story of change. Burying the terrible truth is as ineffective as wishing it hadn’t happened. Naming the horror of sexual violence is a crucial part of the change cycle.

Rape as punishment or as a means of control still lurks in the lives of women. Marital rape is an old story. Date rape is relatively new. In many households, husbands still claim that they own their wives and have the right to sex on demand. Defenseless children are sexually abused by fathers, uncles, and brothers; in some countries, men think that having sex with a virgin girl child will cure HIV/AIDS. The impunity of men when it comes to rape constitutes a centuries-old record of disgrace. For women, sexual violence has been a life sentence.

I’ve spoken to women in Africa and Europe, in Asia and North America about the role of rape in their lives. Some of the stories they told me made me gasp in near disbelief at the extent of the horror inflicted on them. Others made me cheer for the awe-inspiring courage they showed in demanding justice. They all described perpetrators who banked on the silence of society and the shame of the victims to protect them from consequences. But they also spoke of the fearlessness and tenacity it takes to end this scourge.

Some people think you shouldn’t talk about rape. If it happens to you, be quiet, don’t tell, because the stigma could prevent you from getting a job, making new friends, finding a partner. People say, “Put it behind you. There is no good in rehashing the past.” Others still dare to say, “She asked for it. She was dressed like a whore.” Or worse, “She needed to be taught a lesson.” And too many people refuse to accept the statistics. They don’t want to believe that one human being could be so brutal to another human being, so they dismiss the topic as not fit for polite conversation. People who don’t intervene when something is wrong give tacit permission for injustice to continue, proving that there’s no such thing as an innocent bystander.

Rape has always been a silent crime. The victim doesn’t want to admit what happened to her lest she be dismissed or rejected. The rest of the world would prefer to either believe rape doesn’t happen or stick to the foolish idea that silence is the best response.

Today the taboo around talking about sexual violence has been breached. Women from Bosnia, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have blown the whistle about rape camps and mass rapes and even re-rape, a word coined by women in Congo to describe the condition of being raped by members of one militia and raped again when another swaggers into their village. Instead of being hushed up, cases such as that of Mukhtar Mai, the Pakistani girl who was gang-raped by village men who wanted to punish her for walking with a boy from an upper caste, have made headlines around the world. And the raping of an unconscious girl in Steubenville, Ohio, in 2012 got everyone’s attention, mostly because some of the media reported that the “poor boys who raped her were going to jail and their lives were over.” An outraged public responded with a conversation that went viral: “If you’re so worried about your high marks and your great ‘rep’ and your football scholarship, don’t go around raping unconscious girls and posting the photos on YouTube.”

The causes and consequences of rape are at last being debated at the United Nations. The International Criminal Court in The Hague declared rape a war crime in 1998. The UN Security Council decided that rape was a strategy of war and therefore a security issue in 2007. The announcement was welcome news to the activists, but most people asked what the Security Council could or would actually do with their newly forged resolution, which called for the immediate and complete cessation by all parties to armed conflict of all acts of sexual violence against civilians. The resolution also called for states to provide more protection for women and to eliminate the impunity of men. Getting traction on a UN resolution is like hoping for rain in the middle of a drought. Women are fed up with waiting for action. Eve Ensler, the award-winning playwright, author of The Vagina Monologues, and founder of V-Day, the global activism movement to end violence against women and girls, had an idea. What if 1 billion women around the world stood up on the same day and sang the same song and danced the same dance? What if together they claimed their own space, raised their own voices, took back the night? Would that send a message that 50 percent of the population has had it with violence against women? The naysayers said it could never be done. But the naysayers hadn’t asked the world’s women.

On February 14, 2013, 1 billion women from India and the Philippines to the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany danced, sang, and reclaimed their own bodies. On February 14, 2014, they did it again. Thousands of pairs of feet stomping, hands clapping; little kids and grannies, businesswomen and teenagers flooded into public squares in 207 countries. They danced, raised their arms skyward, and sang in a victory chant that was heard all over the world.

I dance ’cause I love,

Dance ’cause I dream,

Dance ’cause I’ve had enough,

Dance to stop the screams

Dance to break the rules

Dance to stop the pain

Dance to turn it upside down

It’s time to break the chain

They were taking part in One Billion Rising, which was the largest global action in history to end violence against women. Like a rising tide, the decision to stop the oppression, the abuse, the second-class citizenship of women was already surging in Asia, in Africa, in North America and Europe. When Eve Ensler did the math, she made a startling announcement: “One in three women on the planet will be raped or beaten in her lifetime. One billion women violated is an atrocity. One billion women dancing is a revolution.”

The idea came to her when she returned to the Democratic Republic of Congo—to Bukavu and the City of Joy she had built with the women who had suffered the worst and likely most depraved abuse the world had ever known. It was a bald and thin Eve Ensler who had just stumbled out of the fog and fear of uterine cancer treatment who fell into the welcoming arms of the women she had worked with in what had come to be known as the rape capital of the world. Eve linked her own cancer to the cancer of cruelty that these women knew. In her new book, In the Body of the World, she describes “the cancer from the stress of not achieving, the cancer of buried trauma” and the epiphany she had that “cancer was the alchemist, an agent of change”: “I am particularly grateful for the women of Congo whose strength, beauty, and joy in the midst of horror insisted I rise above my self-pity.”

It was there she imagined the dance. “It could transform suffering into action and pain into power. We could call on all women to dance, to take back the spaces, put their feet on the earth, reclaim their bodies.” The idea spread like wildfire: urban and rural women, farmers and fishers, artists and teachers all said they would dance.

Eve Ensler says, “Dancing is a genius form of protest. You can do it together or alone, it gives you energy, makes you feel you own the street. Corporations can’t control it.” She lists dozens of events that made up One Billion Rising: a flash mob in the European Parliament, more than forty events in New York City, participation by cell phone in Tehran, a human chain in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and acid attack survivors in that country who rallied and danced. Fifteen city blocks in Manila had to be closed to accommodate more than a million women dancing. Two hundred women and men marched in front of the parliament in Afghanistan. There was the first-ever flash dance in Mogadishu, Somalia, and more than two hundred events in the United Kingdom. Hollywood actors like Anne Hathaway rose up. So did the Dalai Lama and politicians and CEOs. Eve says the participation was beyond her wildest dreams. She’s on a mission to stop the violence that she calls “the methodology of oppression” once and for all. Her goal was to find the right steps to end violence “so it’s not perpetual Groundhog Day.”

One Billion Rising was the wind needed to blow on the coals so the fire would ignite. And now she wants the international community to step up and keep stoking the fire. “Our time has come,” she says. “This is the moment to trust what you know, trust your instinct, move knowledge into wisdom. Now is the moment to stop waiting for permission. Stand up for your truth.” She calls women the people of the second wind and calls on all of us to keep rising.

One Billion Rising isn’t a single assault on violence against women. It’s part of a collection of volleys against sexism and oppression that is gaining in strength around the world today.

One of the most stunning examples comes from Kenya, where in 2011 there was a watershed moment everyone had been waiting for. In the northern city of Meru, 160 girls between the ages of three and seventeen sued the government for failing to protect them from being raped. Their legal action was crafted in Canada, another country where women successfully sued the government for failing to protect them. Everyone from high court judges and magistrates in Kenya to researchers and law-school professors in Canada believed these girls would win and that the victory would set a precedent that would alter the status of women in Kenya and maybe all of Africa.

These are grand claims for redressing a crime as old as Methuselah, but the researchers and lawyers working on the case insisted that the evidence was on their side.

The suit was the brainchild of Fiona Sampson, winner of the 2014 New York Bar Association Award for Distinction in International Law. She is the project director of the Equality Effect, a nonprofit organization that uses international human rights law to improve the lives of girls and women. It came about by way of a touch of serendipity and a lot of tenacity. Sampson was doing a master’s degree at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto in 2002 when she met fellow students Winifred Kamau, a lecturer from the University of Nairobi Law School, and Elizabeth Archampong, vice dean at the Faculty of Law at Kwame Nkrumah University in Ghana, who had come to Canada to study international law. Their mutual interest in equality rights drew the women together. A few years later, when Seodi White, a lawyer from Malawi, was a visiting scholar at the Center for Women’s Studies at the University of Toronto, the trio became a foursome. When the African women wondered if the model used in Canada in the early eighties to reform the law around sexual assault—in which legal activists successfully lobbied to rewrite the law, educate the judiciary, and raise awareness with the public—could work in Africa, Sampson started thinking about ways to tackle the entrenched violence against women in countries like Kenya, Malawi, and Ghana.

Eight years after their initial meeting, the quartet gathered in Nairobi in 2010 with the pick of the human rights legal crop from Canada and Africa for the historic launch of Three to Be Free, a program that targets three countries, Kenya, Malawi, and Ghana, with three strategies—litigation, policy reform, and legal education—over three years in order to alter the status of women. Their intention was to tackle marital rape and make it a crime. But when the lawyers returned home and started their research, another serendipitous meeting took place. A woman named Mercy Chidi was in Toronto taking a course at the Women’s Human Rights Education Institute at the University of Toronto. One of the lawyers working on the marital rape case, Mary Eberts, was teaching the course and heard Chidi’s story. She called Sampson and suggested she meet Chidi, who was the director of a nongovernmental organization called The Ripples International Brenda Boone Hope Centre (which is known locally in Meru as Tumaini—the Swahili word for “hope”). First a word about Brenda Boone, the Washington-based executive whom the shelter is named for. She met Mercy in 2006 when Mercy was in Washington raising money to rescue kids with AIDS who’d been abandoned. “I invited Mercy and her husband to come to my house—they arrived in full African attire in my Capital Hill home that was full of antiques and Victorian furniture.” Brenda asked how she could help, and when they asked her for a computer, she provided one immediately, along with a check for $5,000. A year later, Mercy was back in Washington to receive the International Peace Award. Brenda invited the Chidis back to her home—“I served them fried chicken because it was Sunday and I’m Southern”—and Mercy explained that they had made a business plan and decided to open a shelter for girls who had been raped. “That pierced my heart,” says Brenda. “I gave them another check, this time for $25,000, and committed to financing everything to get the place going.” Brenda knew the missing piece was the legal action required to stop the raping of girls.

A few years later, when Mercy met Fiona Sampson and told her about the shelter and about the girls who can’t go home because the men who raped them are still at large, they both knew it was time to tackle the root of the problem—the impunity of rapists and the failure of the justice system to convict them.

Sampson admits it was her own sense of urgency that made the concept take flight. “I am the last thalidomide child to be born in Canada,” she explains, referring to the anti-morning-sickness drug whose side effects in utero had affected the development of her hands and arms. (The drug was banned in 1962.) “There was a culture of impunity in the testing of drugs at that time,” she explains, “so I’m consumed with the desire to seek justice in the face of impunity.”

Kenya has laws on its books designed to protect girls from rape, or “defilement.” The state is responsible for the police and the way police enforce existing laws. Since the police in Kenya failed to arrest the perpetrators and fail on an ongoing basis to provide the protection girls need, the lawyers filed notice that the state is responsible for the breakdown in the system. Sampson said at the time, “We will argue that the failure to protect the girls from rape is actually a human rights violation, that it’s a violation of the equality provisions of the Kenyan constitution. It’s the Kenyan state that signed on to international, regional, and domestic equality provisions and it’s therefore their obligation to protect the girls. Only the state can provide the remedies we’re looking for, which is the safety and security of the girls.”

Sampson and other human rights lawyers in Canada have done this successfully for approximately twenty-...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherThomas Dunne Books

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1250045282

- ISBN 13 9781250045287

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.49

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Uprising: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mother's Daughter

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # mon0000238487

Uprising: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mother's Daughter

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1250045282

Uprising: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mother's Daughter

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1250045282

Uprising: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mother's Daughter

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1250045282

Uprising: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mother's Daughter

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks443815